More minimally edited notes from Picnic 10.

Adam Greenfield prepared a top selection of panelists for his workshop on ‘networked Amsterdam’. As we sat in one of the Picnic yurts (!!) we heard a series of short presentations on Amsterdam as seen through different technological lens.

First up was Usman Haque (Pachube) who spoke broadly about the sensor-Amsterdam. He reminded us that sensors never provide pure information, instead there are always decisions being made – what to count, what not to. Speaking about EEML (extended environments markup language): data has context, descriptive, numerical, changes over time vs raw. EEML describes context and state. Measuring needs to be discrete continuous and incremental.

Tom Coates (ex-FireEagle) was up next looking at Amsterdam through the lens of data. Showing us the many easily publicly accessible data layers already out the on the web – open street map view of Amsterdam, people and transport movements through RFID tracking in the public transport system of Ovi Chipkart, power consumption, social checkins from Foursquare etc, geotagged Flickr photographs generating Flickr shape files as a people centric view of the world/map – concluding with Aaron Straup-Cope’s/Stamen’s Amsterdam PrettyMaps.

Despite this array of different views the map and terrain are still very distinct. The experienced Amsterdam is not the map so what is necessary to get closer to having the map and the territory merge? Does this begin with unique ids for each building is required to link that map and the territory. Can this apply to the world of objects?

Anab Jain (Superflux) was up next looking at Amsterdam through the lived lens of services. Do we have an ‘App-ocalypse’? Where experiencing the city is through the clumsy lens described by Coates – and thus many of the nuances of the city are obscured and invisible?

Jain contrasted with her experience of India. Here she showed how addresses change and thus how the map is never the territory. The importance of the rickshaw wallah both as guide and multi-service provider – the human version of Google Maps and social recommendation services? And of course seeing these urban actors as key urban services introduces the opportunity for ‘deviant services’. So could mobile services connect people to each other rather than people to machines? The idea of the “open generative city” vs (just) information services – post-efficient services? The criticality of serendipity and diversity of experiences.

Matt Cottam spoke about ‘objects’. Here in Amsterdam the remarkable integrated and holistic design for the Ovi Chipkart RFID transport ticketing system was made possible because of the different cultural system here in Amsterdam. A lack of paranoia about centralisation, and an acceptance of the trade off between utility and privacy. (See also the cultural norm to leave curtains open on domestic houses).

So what becomes possible? Could parking meters also be used to sell event tickets or even report problems with the city streets? They already contain the necessary technology – printer, payment acceptance, Internet connection and screen. Cottam then showed a wonderful sculpture garden of old public utility furniture. These were beautifully ‘designed’ objects, not the functional equivalents that now line the streets. They also seemed far more robust.

Is there an emerging trend towards refillable objects – with well designed innards? The Leica digital upgrade programme as an example?

Cottam concluded by showing the BluDot Real Good experiment which was part of a marketing campaign for BluDot. It focusses on how the city already recycles objects and how well designed objects live many lives.

I started Day Three catching Cory Doctorow (Boing Boing). I admire Doctorow’s persistence as an author whose traditional business models have been radically challenged, to experiment and make his own path in the resulting mess. It is a very American persistence. Thus I wanted to like Doctorow but his style carried such a sense of anger and resentment that it greatly diminished his message. Perhaps it was his jet lag or maybe, like me, he had some travel problems. Either way, being hectored about how iTunes is locking down authors rights on ebooks (preventing them from rejecting DRM) is a tough way to start a morning. Nevertheless I did like his emphasis on authors making the most of price discrimination for ebooks – where different ‘levels’ of ‘experience’ are priced differently. I couldn’t help think of how social finance schemes like Kickstarter are really accelerating the normalisation and visibility of price discrimination.

Steven Emmett followed with a fascinating talk about a programming language for genetic manipulation. in simple terms it looked like this language allows the programming of gene splicing and the ‘printing of genetic sequences’ for splicing. I loved the idea that Emmett presented that it was Bell Labs in the late 1940s with the invention of the transistor that made possible the ICT explosion and that we are in the equivalent of the 1940s now for genetic engineering. Exciting, if unimaginable futures?

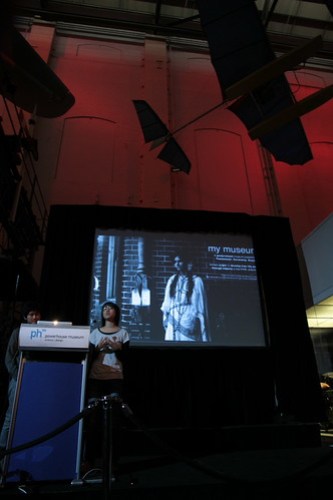

Next it was over to the third of the sessions that I was involved in organising – ‘new business models of digital culture and heritage’. Charlie Leadbeater started off outlining the key ideas in his recent missive, Cloud Culture (available as a free download). For cultural producers these are difficult times – they are reaching more people but making less money, and in the developed world we are living longer but receiving less in pensions.

Leadbeater outlined four types of organisational response to these changes. Strategy one – same goals, different methods; two – different goals, same means; three – same goals, different mix of means; and four – transformational, different goals, different means. The fourth is the most radical but also potentially the most fruitful. Unfortunately, he pointed out, ‘improving’ can be the enemy of transformation – ‘making things better’ brings down the opportunity to make transformational change. Transformation requires reframing the challenges and opportunities and resources. And in the cultural sector this is likely to be mix of new and old.

Harry Verwayen from Europeana outlined Europeana’s strategies going forward. Not organically birthed, Europeana, Verwayen explained was birthed from a highly political European reaction to Google’s mass book scanning efforts. They have changed tack and are clearly searching for productive ways forward now that ’12 million objects’ are online.

Soenke Zehle explored the ways in which cultural actors, and especially institutions could provide a far more ‘critical’ role in addressing the issues highlighted by Leadbeater, as well as the (global) political economy of digital culture. As he stressed, there are going to be winners and losers here – there is no win-win situation. This happens at every layer – the hardware layer where geopolitical tensions and instability around oil are already shifting to countries with rare metals required for the ‘digital economy’; all the way through to the service layer where content producers are feeling the pinch.