At the tailend of February I was invited to address the National Art Educators Association at the Met. I was fresh to NYC and I was in a mood to stir. I spoke about a number of different challenges yet to be properly addressed by the sector – and the one I ended up spending most time on was the opportunities afforded by 3D digitisation and then 3D printing. What, I posed, could be made better for art education if school students could ‘print a work’ back in class? Or, coming as I do from a design museum, students could ‘re-design’ an object by pulling a 3D model apart, prototyping a new form, then printing it to ‘test it’?

Little did I know that a few months later, Don Undeen’s team at the Met itself would hold an artist-hack day to use consumer-grade tools to digitise and print certain works. Their event set off quite a wave of excitement and experimentation across the sector, and fired the imaginations of many.

Liz Neely, Director of Digital Information & Access at the Art Institute of Chicago (not), has been one of those experimenting at the coal face and I sent her a bunch of questions in response to some of her recent work.

Q – What has Art Institute of Chicago been doing in terms of 3D digitisation? Did you have something in play before the Met jumped the gun?

At the Art Institute before #Met3D, we had been experimenting with different image display techniques to meet the needs of our OSCI scholarly catalogues and the Gallery Connections iPad project. The first OSCI catalogues focus on the Impressionist painting collections, and therefore the image tools center on hyper-zooming to view brushstrokes, technical image layering, and vector annotations. Because the Gallery Connections iPads focus on our European Decorative Arts (EDA), a 3-dimensional collection, our approach to photography has been decidedly different and revolves around providing access to these artworks beyond what can be experienced in the gallery. To this end we captured new 360-degree photography of objects, performed image manipulations to illustrate narratives and engaged a 3D animator to bring select objects to life.

For the 3D animations on the iPads, we required an exactitude and artistry to the renders to highlight the true richness of the original artworks. Rhys Bevan meticulously modelled and ‘skinned’ the renders using the high-end 3D software, Maya. We often included the gray un-skinned wireframe models in presentations, because the animations were so true it was hard to communicate the fact that they were models. These beautiful 3D animations allow us to show the artworks in motion, such as the construction of the Model Chalice, an object meant to be deconstructed for travel in the 19th century.

These projects piqued my interest in 3D, so I signed up for a Maya class at SAIC, and, boy, it really wasn’t for me. Surprisingly, building immersive environments in the computer really bored me. Meanwhile, the emerging DIY scanning/printing/sharing community focused on a tactile outcome spoke more to me as a ‘maker’. This is closely aligned with my attraction to Arduino — a desire to bring the digital world into closer dialogue with our physical existence.

All this interest aside, I hadn’t planned anything for the Art Institute.

Mad props go out to our friends at the Met who accelerated the 3D game with the #Met3D hackathon. Tweets and blogs coming out of the hackathon-motivated action. It was time for all of us to step up and get the party started!

Despite my animated—wild jazz hands waving—enthusiasm for #Met3D, the idea still seemed too abstract to inspire a contagious reaction from my colleagues.

We needed to bring 3D printing to the Art Institute, experience it, and talk about it. My friend, artist and SAIC instructor Tom Burtonwood, had attended #Met3D and was all over the idea of getting 3D going at the Art Institute.

On July 19th, Tom and Mike Moceri arrived at the Art Institute dock in a shiny black SUV with a BATMAN license plate and a trunk packed with a couple Makerbots. Our event was different from #Met3D in that we focused on allowing staff to experience 3D scanning and printing first hand. We began the day using iPads and 123D Catch to scan artworks. In the afternoon, the two Makerbots started printing in our Ryan Education Center and Mike demonstrated modelling techniques, including some examples using a Microsoft Kinect (eg).

We also did the printing in a public space. Onlookers were able to catch a glimpse and drop in. This casual mixing of staff and public served to better flesh out public enthusiasm. In the afternoon, an SAIC summer camp of 7-9 year olds stopped by bringing their energetic minds. They were both completely enthralled and curiously bewildered by the process.

The event was a great success!

Colleagues began dialoging about a broad range of usages for education programs, creative re-mixing of the collection, exhibition layout planning, assisting the sight impaired and prototyping artwork installation.

Q – Your recent scan of the Rabbit Tureen used a different method. You just used existing 2D photos, right? How did that work? How many did you need? How accurate is it?

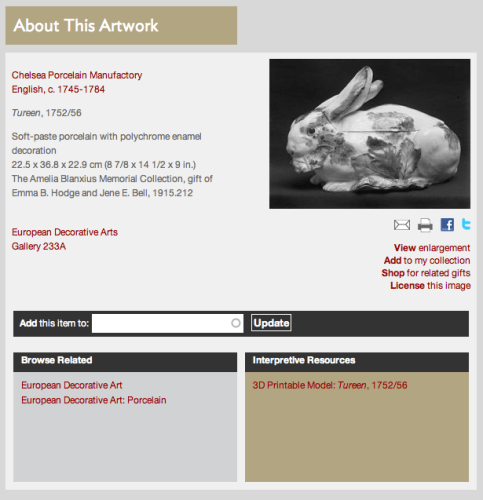

In testing image uploads onto the Gallery Connections iPad app, this particular Rabbit Tureen hypnotised me with its giant staring eye.

Many EDA objects have decoration on all sides, so we prioritised imaging much of work from 72 angles to provide the visual illusion of a 360 degree view like quickly paging through a flip book. It occurred to me that since we had 360 photography, we might be able to mold that photography into a 3D model. This idea is particularly exciting because we could be setting ourselves up to amass an archive of 3D-printable models through the museum’s normal course of 2D sculptural and decorative arts photography.

This hypothesis weighed on my thoughts such that I snuck back into the office over Labor Day weekend to grab the full set of 72 image files.

Eureka! I loaded the files into 123D Catch and it created a near perfect 3D render.

By ‘near perfect’, I mean that the model only had one small hole and didn’t have any obvious deformities. With much Twitter guidance from Tom Burtonwood, I pulled the Catch model into Meshmaker to repair the hole and fill in the base. Voila-we had a printable bunny!

The theory had been proven: with minimal effort while making our 360 images on the photography turntable, we are creating the building blocks for a 3D-printable archive!

Q – What do you think are the emerging opportunities in 3D digitisation? For education? For scholarship? Are curators able to learn new things from 3D models?

There are multitudes of opportunities for 3D scanning and printing with the most obvious being in education and collections access. To get a good 3D scan of sculpture and other objects without gaping holes, the photographer must really look at the artwork, think about the angles, consider the shadows and capture all the important details. This is just the kind of thought and ‘close looking’ we want to encourage in the museum. The printing brings in the tactile nature of production and builds a different kind of relationship between the visitor, the artwork and the derivative work. We can use these models to mash-up and re-mix the collection to creatively explore the artworks in new ways.

I’m particularly interested in how these techniques can provide new information to our curatorial and conservation researchers. I’ve followed with great interest the use of 3D modelling in the Conservation Imaging Project led by Dale Kronkright at the Georgia O’Keeffe museum.

Q – Is 3D the next level for the Online Scholarly Catalogues Initiative? I fancifully imagine a e-pub that prints the objects inside it!

A group of us work collaboratively with authors on each of our catalogues to determine which interactive technologies or resources are most appropriate to support the catalogue. We’re currently kicking off 360 degree imaging for our online scholarly Roman catalogue. In these scholarly catalogues, we would enforce a much higher bar of accuracy and review than the DIY rapid prototyping we’re doing in 123D Catch. It’s very possible we could provide 3D models with the catalogues, but we’ll have to address a deeper level of questions and likely engage a modelling expert as we have for the Gallery Connections iPad project.

More immediately, we can think of other access points to these printable models even if we cannot guarantee perfection. For example, I’ve started attaching ‘Thing records’ to online collection records with associated disclaimers about accuracy. We strive to develop an ecosystem of access to linked resources authored and/or indexed for each publication and audience.

Q – I’m curious to know if anyone from your retail/shop operations has participated? What do they think about this ‘object making’?

Like a traveling salesman, I pretty much show up at every meeting with 2 or 3 printed replicas and an iPad with pictures and videos of all our current projects. At one meeting where I had an impromptu show and tell of the printed Art Institute lion, staff from our marketing team prompted a discussion about the feasibility of creating take-home DIY mold-a-ramas! It was decided that for now, the elongated print time is still a barrier to satisfying a rushed crowd. But in structured programs, we can design around these constraints.

At the Art Institute, 3D scanning and printing remains, for now, a grass-roots enthusiasm of a small set of colleagues. I’m excited by how many ideas have already surfaced, but am certain that even more innovations will emerge as it becomes more mainstream at the museum.

Q – I know you’re a keen Arduino boffin too. What contraptions do you next want to make using both 3D printing and Arduino? Will we be seeing any at MCN?

Ah ha! This should be interesting since MCN will kick off with a combined 3D Printing and Arduino workshop co-led by the Met’s Don Undeen and Miriam Langer from the New Mexico Highlands University. We will surely see some wonderfully creative chaos, which will build throughout the conference.

These workshops may seem a bit abstract at first glance from the daily work we do. I encourage everyone to embrace a maker project or workshop even if you can’t specifically pinpoint its relevance to your current projects. Getting your hands dirty in a creative project can bring and innovative mindset to e-publication, digital media and other engagement projects.

Sadly I won’t have time before MCN to produce an elaborate Arduino-driven Makerbot masterpiece. I’m currently dedicating my ‘project time’ to an overly ambitious installation artwork that incorporates Kinect, Arduino, Processing, servos, lights and sounds to address issues of balance ….