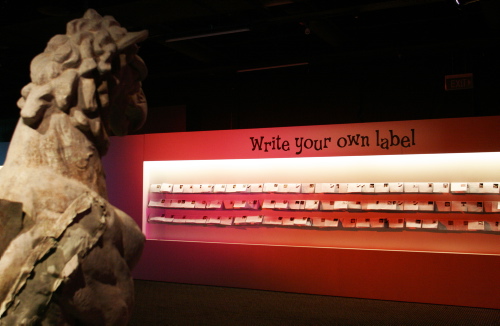

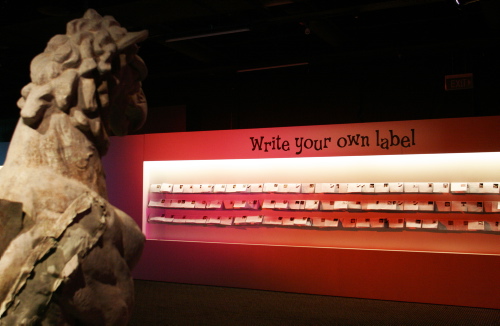

At the Powerhouse we’ve just launched something called The Odditoreum. An incredibly low-tech “exhibition” with no technology-based interactive experiences and minimal web presence, The Odditoreum feels remarkable for the level of participation it is engendering. Visitors are actively writing their own labels for the objects and even before launch there was a lot of interest when Paula and Erika blogged about seeing some of them in the workshop.

I spoke to Helen Whitty, Public Programs Producer, about the project.

F&N: What is The Odditoreum?

HW: The Odditoreum is a moveable feast whose essential ingredients are a selection of collection objects and a well known author – Shaun Tan. Combined they have made a small exhibition, book, limited edition print and the core of the July school holiday program.

The Museum allocates significant resources to our quarterly school holiday programs and on the whole I think we do great holiday programs and we work hard to maintain the standard regardless of whether that particular holidays are minor or medium size.

The motivation for the theme of the July period came about because the Museum did not have a new temporary exhibition to promote. Nor had we changed much of our permanent exhibitions for children for many years. The specialist facilities of Zoe’s House and The Magic Garden are an exception and had both already been covered in prior holidays.

The Odditoreum’s small exhibition component is 18 ‘odd’ objects that are not currently in storage. Shaun Tan, a celebrated author was invited to write ten of the labels (in fact that’s all he said he had time to write – then wrote eleven). Seven labels were written by young children (from Stanmore Public School) to inspire other visitors to write their own ‘labels’ during the holidays.

The brief for Shaun was to write about 100 words for each object and he could write whatever he liked about each one. I sent him a package with about 20 objects to choose from, each with a photo and extracts from their official documentation file.

He selected those with the most potential to respond to his touch.

F&N: Tell us a little bit about Shaun Tan. Where did you come across Shaun’s work before?

I love children’s books and could barely resist purchasing stacks for my own children. For years I’d been angling to incorporate children’s authors into my programming.

Shaun Tan’s work is a particular family favourite and I thought the imagery in The Lost Thing could have had the Powerhouse in mind. His stories are often simple, elegant and profound – with extraordinary illustrations. I had contacted Shaun a couple of times to work on projects but whilst interested, he was always too busy.

He told me he was attracted by the name (Odditoreum) and ’10×100 word’ labels felt achievable within his busy schedule. The possible material he was sent to work with intrigued him.

Shaun’s writing style can be quite dark as a way of being thought provoking. He told me that happy, or at least fully resolved endings don’t stay with the reader, don’t prompt them to look for alternate scenarios. I like that.

As for the reader – he doesn’t see himself as an author for children necessarily. He describes his audience as:

‘…anyone who is curious, who enjoys strangeness, mystery and oddity, who likes asking questions and using their imagination…[I always ask myself] what are the ways that something can be represented to most effectively invite us to think and ask questions about the world we live in.’

I think he describes the spirit of what we try to do with our work with visitors.

F&N: How were the objects chosen?

At the end of the day the final selection was going to be determined by –

– the available showcases (my initial planning submission referred to ‘within existing infrastructure’ — I love that expression, basically saying ‘its gunna be cheap’ in business plan speak).

– the location and whether it was easily moved (there goes the front window of the passenger jet)

– conservation and display requirements (did I mention cheap?)

– was it intended to be lent out or used in a planned exhibition (unlikely)

– part of a tour for our offsite open storage (yes, the prawn on a bicycle is part of the schools technology offer – sigh)

– sensitivity of donors and/or curators

And ultimately Shaun’s selection.

There were certainly a few of my favourite things in the array.

I don’t claim to know the collection but I have prowled the basement on many occasions for books I’ve authored for the Museum. And not being a curator I wasn’t tied to any particular area (though I do find myself strangely attracted to Z4). I used OPAC. I even circulated an email titled ’31 odd heads are better than one’ to our curators, and sent begging emails to registrars. Many responded.

Suggestions came from carpark conversations, voice messages (“have you seen what’s sitting outside the Transit Room lately?”) and so on. I didn’t actually look in the stores this time, as to be honest I was fitting all this in between too many jobs — but in the end this chaotic series of conversations threw up a lot of interesting stuff.

I gathered up a little selection team (Rebecca, my champion from Exhibition Coordination, Judith, a Casual Assistant and mother of young children (nothing casual about her), Alison (an expert Registrar), Malcolm (our ‘silk purse out of sows ear’ exhibition designer) and we sorted through the piles of images, object numbers and descriptions.

In my head I was looking for things that had some familiarity to a child but looked a bit strange or were made of strange materials. I felt I wanted the selection to come from different collection areas (rather than, say, all clothing) and also from different time periods — so things weren’t odd just because they were old.

I also felt the backstory should be interesting (“oh that’s what it is!”).

The most obvious thing we should have done was to invite children to make the selection. I thought about it but time was slipping away and in retrospect I let go of this idea too easily.

What we all found hilarious was what people thought was odd, and not.

Someone had suggested the barbed wire display which I found a bit odd, but at which a curator commented …’what’s strange about that? Its not even the best collection of barbed wire in Australia’ and I imagined the label could simply read “The second best collection of…”. We didn’t present the barbed wire to Shaun as the Conservators all shuddered, though I think he would have loved it.

And I paused to think about oddness being about lack of familiarity – who know, rural kids may have found the barbed wire too ordinary for words!

In the end things were dropped as they wouldn’t fit or they just got left behind. I miss Lucky Starr’s star shaped guitar as I would have liked a musical instrument

Maybe there’s a bit of ‘curator’ in us all.

And even then some peculiar things arose after the final choice was made.

Sue Gatenby writes “A slide collection of unusual microscopic specimens were selected for display in the Odditoreum exhibition. Amongst this collection was a microscope slide containing a blood smear from an Anthrax patient from the 1890’s. This slide was assessed for its risk. Several specialists were contacted including Dr. Andrew Holmes, Senior Lecturer, Molecular Microbial Ecology at the University of Sydney and the Office of Gene Technology Regulator (OGTR) – transport of Genetically Modified Organisms (GMO). The risk assessment and management, including the storage and handling guidelines. It was determined that the Occupational Health & Safety risk was low and with the recommended storage and handling guidelines the slide can remain in the collection.”

F&N: How did Shaun approach the labels?

When I first approached him I sent him about 6 images to whet his appetite and with out me asking he sent back labels for the prawn on the bicycle; the shirt from Cameroon covered in human hair and the giant model of the garden pea. I think these objects caught his eye or in the case of the shirt it just sounded weird.

He was interested in the official file information I sent him and the back story did inform his writing. He was less interested in the objects that were made by an artist or designer. He argued that these already had the overlay of an interpretation which he would need to break through. So he didn’t do the Encyclopaedia of Dresses or the Vivienne Westwood shoes.

The exception was the Liquorice Allsorts Shoe (a parade bicycle made for the Sydney Olympic Games Opening Ceremony). In Victoria they still use Guard Dog Collection boxes. Shaun often throws change into the one at his local shop and Somehow the two images folded together into this combinatory label text:

Guide dog testing device number 6

This enormous liquorice all-sorts shoe is one of several outlandish objects used to test young guide dogs for their susceptibility to distraction while on duty. A tricycle inside the shoe allows a rider to manoeuvre this colourful vehicle while prospective guide dogs are put through their paces. The shoe appears at the moment an important task needs to be performed, such as crossing a road, laying quietly in a restaurant, or entering a lift. Dogs are then assessed on their ability to maintain composure and focus, thus preparing them for the challenges of the real world.

Other ‘canine distracters’ commonly used by training staff include a Volkswagen covered in sausages, an ice-cream van that spills colourful rubber balls, and a litter of kittens riding on a miniature steam train.

Shaun wrote them up and Judith Matheson (Editorial and Publishing — “all authors are edited Helen. I’ll only do a light edit…”) did indeed tidy them up expertly for their final label.

The actual format of the label was chewed over as they were to be larger and we did think about appropriate reading fonts for children and included a picture of the object. Christina Fedrigo was the Graphic Designer across all media and had a wonderful feel for the spirit of the project.

F&N: The exhibition is very frugal – it uses an otherwise vacant gallery, and there is a lot of ‘space’. Tell me about this. How cost effective was it?

The Odditoreum did not start out as an exhibition. It was put up as a public program with a small display for school holidays. Being a public program it was more or less in my control and budget. In the past (though this is changing) public programs were not subject to the same level of scrutiny as an ‘exhibition’.

Exhibitions are on longer – they are more expensive, they have donors and sponsors and layers of stated and assumed reciprocal arrangements and protocols that can make them the jewels that they are.

But I also feel they are seen as more significant or of a higher order than their “frivolous cousins” – that is public programs who are mostly doing stuff for families.

I felt I could pull off a program for July whilst an exhibition would need to be scheduled and polished and is so doing quite possibly might disappear. In the end the Project Submission which proposed a gamut of outcomes was enthusiastically approved and supported to a level not previously experienced.

The display of objects was intended to sit within a fairground space in a highly trafficked area of the Museum. It was a decision of the Executive later to move it into a gallery and that is about when I stopped calling it a display.

It took on the persona of a small exhibition which cost about AU$7000 (excluding staff time).

I was nervous when it was decided to move it from a programming area into a gallery as I felt it would need additional funds for an ‘entry experience’ and I wasn’t sure how the objects would sit in another context and whether the ‘existing infrastructure’ would really just ‘look cheap’.

But on the other hand it has been great to run the experiment – which isn’t over yet, it is only just beginning – and so far it ‘reads’ like an incredibly cost effective exhibition.

F&N: I imagine that this is quite a radical shake up of a traditional exhibition – although I understand non-museum types ‘get it’ pretty much straight away. Were there conflicts over objects between the public programs team and curatorial?

Initially I heard that there was concern from some curatorial quarters about this approach, but none directly to me. As curatorial staff apply focused attention to these matters and indeed caretake the collection they were concerned that the proper checks and information wouldn’t be included into the process. I also think that sometimes the ‘caretaker role’ of curators sometimes drifts into an ‘owner role’ (if only unconsciously).

The Cameroon Hair Shirt was put forward indirectly as a potentially problematic object as it may have had spiritual, if not ceremonial, associations for some communities. We simply didn’t know.

My view on this was that we should put any ‘odd’ objects forward without this sort of censorship (the exception being secret sacred objects that we would not be putting on display anyway). The shirt had already been on show. So I decided to try and censor the choices as little as possible. And I had faith in Shaun Tan.

Whilst his labels would be quirky at a deeper level they would still be respectful.

But these concerns did not really eventuate into even a formal conversation, as I think this new method, if you like, was digested.

Directly curators have been extremely positive and curatorial involvement has been to suggest objects and then to check if my ‘real’ object description was correct.

F&N: How did curators and others in the museum respond to the ‘fictional’ labels? How long did it take for them to get on board?

I wanted children and families to be curious enough about the objects to want to find out what they were and demand to know — wouldn’t that be great! But I didn’t want the fantasy label immediately next to the real information, thus spoiling the approach (‘really you thought we were going to fun but really its business as usual’).

We can be so didactic in our approach to the extent that we overstate the obvious, for example directions that say “Look around the exhibition to find out more”.

The Curators and Editorial did want the real information nearby and it was starting to surface as a point of conflict. But after interviewing Shaun and showing children I realised that part of the joke (if you like) was knowing what they really were. At the end we put this info in another format nearby (not on top of) and written in a very child-friendly style.

F&N: How has the public responded? When I visited the entire ‘make your own label’ wall was full!

The public response is amazing. I think we have really tapped into something with this approach.

All ages are writing.

It is clear from their own labels that they are reading all the information and thinking about it. It is as though we have put out the invitation in such a way that they want to respond.

Here is one of the (edited) labels about Object 17431–1, a ball of puree, purchased in 1887, from the children at Stanmore Public School. I think this also gave everyone confidence to write.

Elephant’s wee

This lovely little ball is a great treat for all to eat. Made out of pure elephant wee, it is a luxury and only served at the finest of places. It was discovered in Africa in an elephant café when an elephant peed in a glass and another elephant drank and said it was good! So the elephant chef figured out how to make it into a great treat!

It then made its way to humankind and I guess some one drank it and liked it and sold it to the museum where it is now. If you want to try it, eat it now at your closest elephant restaurant shop.

Augustine, aged 9

Stanmore Primary School

F&N: This reaction doesn’t seem to ‘just be kids’ – despite this being clearly identified as a ‘for kids’. Do you think that this sort of ‘fictional’ museum can scale? Could you have an entire museum created as an ‘experience’ in this way?

That’s a good question and I’m not quite sure at this stage.

I think putting something different in makes you relook at it all. By considering what’s odd you consider what is ‘normal’ if you like. It is the juxtaposition of approaches that is effective.

Possibly because it is in a ‘kids exhibition’ it gives permission and confidence for adults to write. Or perhaps Shaun’s own ethos about who he writes for is coming back as who is responding to it;

‘…anyone who is curious, who enjoys strangeness, mystery and oddity, who likes asking questions and using their imagination’

Thanks to Helen Whitty for the interview and Paula Bray for the photographs.

If you are in Sydney, pop in and see the Odditoreum and tell us what you think!