I like the notion that Noam Cohen raises in his recent New York Times article where Wikipedia is compared to a city.

It is this sidewalk-like transparency and collective responsibility that makes Wikipedia as accurate as it is. The greater the foot traffic, the safer the neighbourhood. Thus, oddly enough, the more popular, even controversial, an article is, the more likely it is to be accurate and free of vandalism. It is the obscure articles — the dead-end streets and industrial districts, if you will — where more mayhem can be committed. It takes longer for errors or even malice to be noticed and rooted out. (Fewer readers will be exposed to those errors, too.)

Like the modern megalopolis, Wikipedia has decentralised growth. Wikipedia adds articles the way Beijing adds neighbourhoods — whenever the mood strikes. It is open to all: the sixth-grader typing in material from her homework assignment, the graduate student with a limited grasp of English. No judgements, no entry pass.

When most of us take a look at Wikipedia we conveniently forget that behind the names that create and edit the articles are real people. Likewise when we are critical of how Wikipedia works (or doesn’t) we forget that Wikipedia is as flawed (or as great) as people are.

And if you were setting up in a new city you would meet with the city and community leaders, then head out and meet those who make the city function – the recommenders, community activists, the outspoken voices (and, depending on the neighbourhood, the kingpins and warlords!). Before all that, of course, you’d be out in the streets working out who and where all these key figures were, and getting a feel for it all. Alternatively, you might approach a city completely from the bottom-up. In so doing you might get lucky or you might also be led into a dark alley and mugged.

So, when Liam Wyatt, Vice President of Wikimedia Australia approached the Powerhouse to be the inaugural venue for a ‘Backstage Pass’ idea we jumped at the chance to put some real world faces to the avatars, and to learn how the nuts and bolts of Wikipedia works from the perspective of those who edit and improve it. We knew Liam from his work with the Dictionary of Sydney and thus knew he was aware of the complexities of the heritage sector.

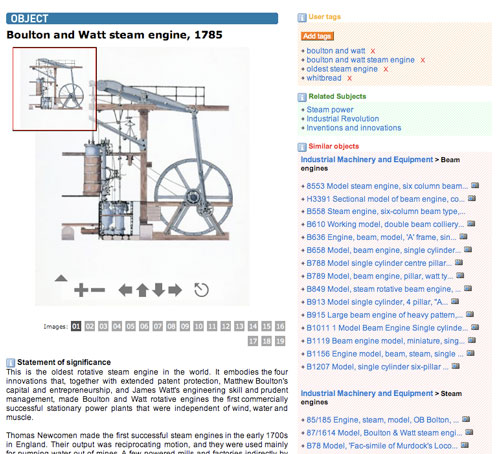

(image by Paula Bray, Powerhouse Museum, CC-BY-SA)

From our perspective, Wikipedia is hugely important. Wikipedia is the highest referrer of traffic to our main website after search. Regardless of whether all our research staff are personally enamoured with Wikipedia, it is clear that our research output is made more visible by being cited in Wikipedia. In fact, if citations are a measure of the success of academic research then perhaps Wikipedia citations are a measure of ‘assumed authority’ and accessibility. (More on that in my metrics workshops though!).

At the same time word has it that laptops destined for high school students across the State may come pre-loaded with a snapshot of Wikipedia, so it makes sense for museums to have their knowledge linked and connected to as many relevant articles as possible.

Around the same time as Liam approached the Powerhouse, Shelley Bernstein at the Brooklyn Museum asked us to participate in Wikipedia Loves Art. We really liked the idea but had two organisational issues – firstly, we don’t (currently) “do” art; but most importantly our onsite photography policy needed to be clarified and within the short time frame that wasn’t going to be possible (we are still working on it!). Shelley’s been blogging about the experience of WIkipedia Loves Art over on the Brooklyn blog – and that more open approach to the ‘city’ that is Wikipedia has yielded interesting and complicated results.

So on the 13th of March, Liam rolled up with a motley group of Wikipedians – the youngest was only 13 years old (we hope had a sick note for his teachers!) – and the curatorial staff, along with a photographer, set about giving them a guided tour of the Museum and then our basement collection stores before retiring to a networked meeting room to exchange ideas. All up we ended up dealing with a very manageable group of ten Wikipedians. These weren’t just any Wikipedians, they were paid up members of Wikimedia Australia – the kind of the community leaders you might want to get onside in your neighbourhood.

This made a huge difference.

Even so, Wikipedians are a diverse bunch and like normal people they don’t necessarily understand all the intricacies of how museums work – the timescales, the processes, the conception of significance, the complexities of Copyright in museums. They don’t all agree about the solutions to licensing – and collectively we have widely varying opinions about the viability and usefulness of Wikipedia’s ‘neutral point of view’.

(image by Paula Bray, Powerhouse Museum, CC-BY-SA)

(image by Paula Bray, Powerhouse Museum, CC-BY-SA)

But, as we learnt about how Wikipedia editors think about how to document and improve articles in Wikipedia, our Museum staff spoke of how we document, classify and research. Unsurprisingly between the Wikipedians and the Museum staff we found a lot of common ground.

One of the Wikipedians who came, Nick Jenkins, generously wrote on the Wikimedia-AU listserv,

It was very interesting, and the amount of material and knowledge (at the museum, in the heads of the curators, and in the internal databases at the museum) is truly vast; but the issues that are being grappled with seemed (from my perspective) to be how to fulfil the museum’s mission in an increasing online environment; how that relates to the Wikipedia and finding areas where there’s a good synergy and commonality of purpose, and also questions and complexity of licensing (for images of items and details about items), and all the cultural issues of interfacing the two different cultures and ways of operating.

I thought it was a very positive day, and I left very much with the impression that these were good people who genuinely wanted to help.

From our perspective, the Museum has a whole lot of changes being actively made to Wikipedia articles incorporating its areas of expertise, but most importantly, we’re putting faces to names and beginning to understand the safe and unsafe areas of the city that is Wikipedia.

(image by Paula Bray, Powerhouse Museum, CC-BY-SA)